into the Cambodian jungle

Well, Cambodia was something.

From Hanoi, Dan and I made our way to Siem Reap to meet our friends Jack, Daniel, and Breton from Stanford. Siem Reap is the gateway to most of Cambodia's ancient temples in the north that survived the cultural purge of the Khmer Rouge. Though we'd heard it described as a necessary evil to get to Angkor Wat, one such temple, it ended up being a cool, offbeat touristy area that had the vibe of a beach town without the beach.

Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom are the two largest temples, both built in the 12th century, and are the main tourist draw in Cambodia. Because I know you're curious, here are the fun facts on the temples:

- Angkor Wat is the largest religious monument in the world, measuring 162.6 hectares in size.

- It is the only national monument on a national flag, that I know of.

- Angkor Wat and Thom were constructed in the roaring boom days of the 1100's, a great time to be an ancient Cambodian, which was before the signing of the Magna Carta, for those of you keeping score at home.

- Banteay Srei, one of the more northern temples, dates back to the 900's, pre-Y1K.

We made plans on NYE to catch the first sunrise of the year over Angkor Wat...

...after we slept through those plans, we got up and went to see it around 3pm.

As you can see from the photos...

...we spent a lot of time at temples.

Pictured here: Banteay Srei.

This is also Banteay Srei.

On one of the more interesting days of our three-day temple exploration pass, four of us rented motorbikes and took off for the north to explore Banteay Srei temple and the Cambodian countryside. Cambodia is not the largest country, so we were able to make it almost to the northern border with Thailand before we found that the key had fallen out of Jack's bike and it would no longer start. Fortunately, we were only about 100km from our hostel, which gave Dan and Jack time to share a romantic ride back doubled-up on his bike, after we locked Jack's bike at the site of the lost key.

It was about here that Jack realized his bike was now keyless. (p/c: Dan Bohm)

At this point, losing things has become an almost requisite part of our trip. We backpack in much the same style as the Ship of Theseus, consistently losing pieces as we go and picking new ones up, so that if we ever make it home, we'll arrive with nothing we left with. Losing the key to Jack's bike did afford us one of our most interesting travel experiences, though.

Into the Jungle

When we returned our bikes at night, the owner refused to accept them until we brought back the fourth. After some negotiation, we agreed to rent a truck with his mechanic to fetch it. We rode into the jungle night to get the scooter back with the young man, who gave his name as Boy.

After an initially frosty start, where we minded our own American business and he minded his Cambodian business, we bonded over some songs on the radio and he began to open up. He was only 26, but had worked in the police force before leaving to become a mechanic and work in the travel industry. He talked about wanting eventually to open up his own repair shop and become a business owner, after saving money to return to school for business. He also took flying lessons to become a pilot, but didn't have the money to pursue a license or further education at a university, which is apparently what usually scuttles career plans in Cambodia.

He also had an interesting domestic situation, living with a Japanese girlfriend 10 years his senior. She moved to Cambodia two years ago (6 years after the death of her former husband), but has been reluctant to get a job since moving, and so he supports her on his mechanic's salary.

What he opened up about the most, and perhaps most surprisingly, was the massive corruption in Cambodia, from the police up to the president. He let us know that the president, Hun Sen, lost the popular vote but strongarmed himself back into power. His brother is head of the army, navy, and police of the country, which probably helps. In addition, he helps all his family members out in unrelated business matters, encouraging further corruption in the country. (This was all according to our mechanic friend, but a cursory Wikipedia search reveals that "Hun Sen has been described as a dictator who has assumed authoritarian power in Cambodia using violence, intimidation and corruption to maintain his power base." He was also in the Khmer Rouge, which we'll touch on in a few minutes.)

A doctor that Boy knows was killed for speaking out against the president in newspaper editorials. The police then fat-fingered the investigation in a way that obstructed his family from ever getting justice.

According to Boy, doing anything in Cambodia requires corruption. Per his example, $1 million for building new roads only allocates about $50k to the actual roads, and the rest to bribes. Boy tried to get a job working at the airport, but would have had to pay a $5k bribe just to get the position, which would have taken him a year of earnings to pay back. (Sidenote: this anecdote was to become very relevant for my later time in Cambodia.)

In addition, the land use and deforestation that is so rampant in the country adds to the common people's misery. Per Boy, people who've lived in their homes for 30+ years are now getting kicked out by corporations who buy the land out under them and bribe police to favor their claims, so that they can cut down local forests. While these large corporations win the rights to deforest Cambodia, if people individually cut down trees for building anything, they get arrested for it and have to bribe their way out. While driving through the jungle, we saw people logging on the side of road under cover of night so that they wouldn't get caught.

Perhaps because they have lower ethical hurdles to jump through at home, the companies that win land rights in Cambodia tend to be Japanese and Chinese logging co's making the most investment in Cambodia and causing its deforestation. In addition, Vietnamese companies responsible for running the tourist areas get 60% of the proceeds from the monuments at Angkor Wat.

The veracity of all the above claims is tough to determine. While it seems like much of what Boy told us was true - especially regarding the rampant corruption and presidential abuse of authority - other parts were tough to decipher. What was surprising to us was that this had been our first real chance to speak with a local on our trips outside of the service industry, on the real issues and backdrop of life in a country away from the bright facade of tourism. As I'd come to find out, Cambodia has a lot of serious issues.

Signs advising tourists on responsible voluntourism at the Footprints Café.

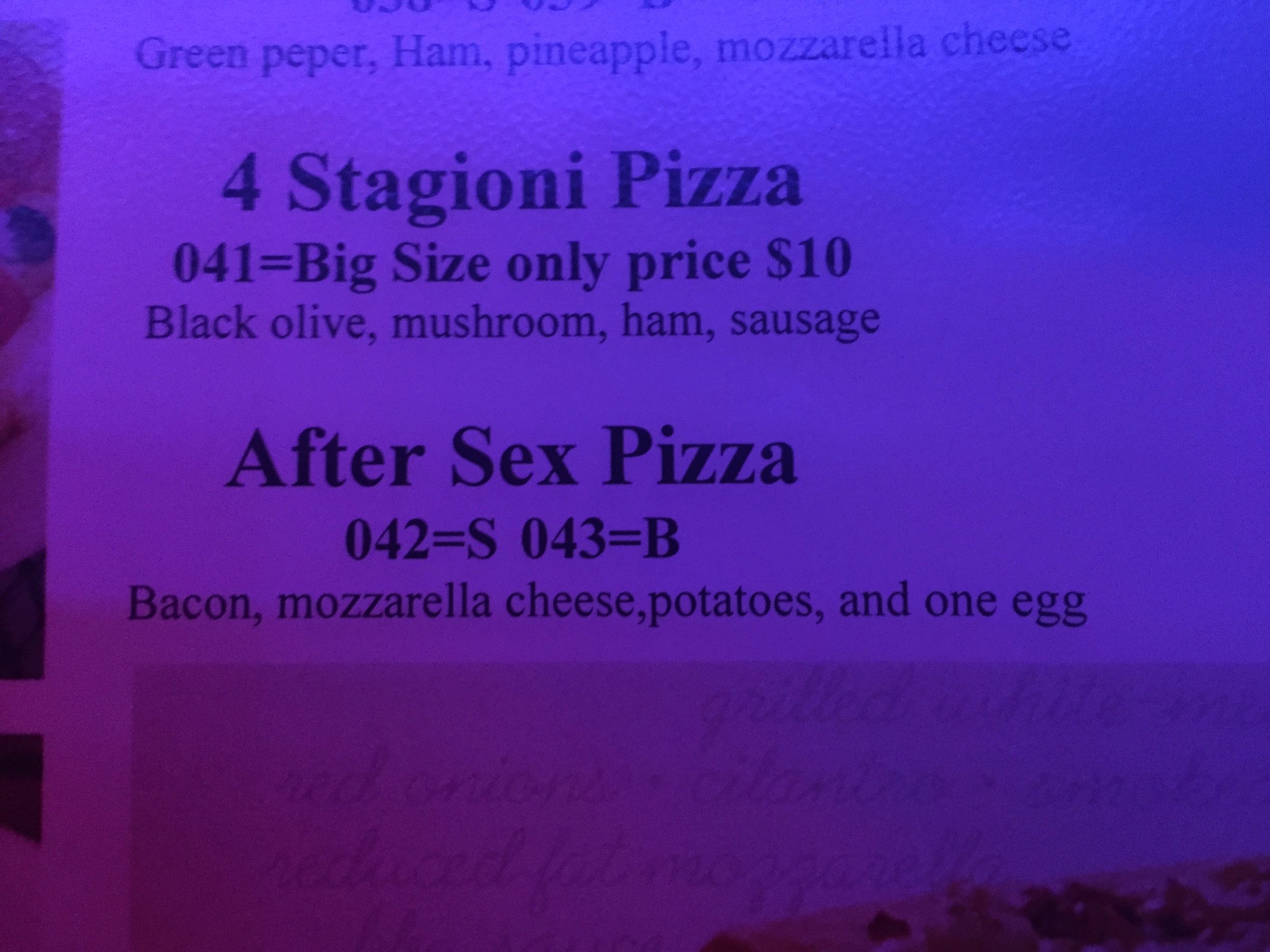

I'll try anything once.

Siem Reap also acts as the hub for a number of NGO's and community organizations that work to improve Cambodia. Our go-to coffee refuel spot in town was Footprint Café, a business started by a British philanthropy group that, among other things, donates 100% of its net profits as educational grants back to the local community, hires locals to run the café (while providing training and career progression, paying a living wage, and offering paid parental leave and health insurance), and uses environmentally sustainable practices (and has a rad lending library in the café.) The parent company is using Siem Reap as a model to try to expand to other countries in SE Asia.

Cambodia is home to a large number of microfinance groups, which is one of my core interest areas. These groups all work on variants of the established Grameen Bank model to slowly lift Cambodians out of poverty and get them onto the "financial grid" through small personal and business loans. I reached out to a couple such groups, Kredit Microfinance and AMK Microfinance, about visiting their offices to interview them, but unfortunately was not able to make it happen.

In Siem Reap, we met a great group that had traveled to Cambodia from Gold Coast, Australia, to build houses with an NGO called Volunteer Building Cambodia. One of them, an Australian of Cambodian descent named Drew, introduced us to the organization. When I worked with Habitat for Humanity, it was rare for volunteers normally to both the start and completion of a house. With VBC, which is one of the only Cambodian-owned NGO's, houses are completed in under a week; volunteers can begin building on Monday and bless the house for living with monks on Friday.

Rules are rules. (Please note that I am not the 70-year Serbian adult baby referenced above.)

Siem Reap is the capital of good sign phrasing.

With Dan taking off to sail with his family in Thailand, I met a young woman from Uganda and traveled with her down to Sihanoukville and Koh Rong, a beach and small island in the south. The beaches in the south were amazing; the clientele not as much. The area serves as the destination of choice for the collective wayward hippies of southeast Asia, which would be great if these were the enterprising hippies that wanted to give back to the local community and build an open, communal way of living. Unsurprisingly, these were instead the kind of hippies who wanted to permanently avoid sobriety and showers. On the plus side, we got to see two hooligans get into a drunken fistfight in our hostel lobby one day before 10am.

I traveled to south Cambodia with an amazing girl from Uganda, who had been traveling for 11 months. Her stories gave eye-opening perspective on how easy it is to travel as an American compared to the rest of the world: repeatedly in Cambodia and the rest of Asia, she was accosted by shopkeepers who harassed her for being a black African. In India, she was denied entrance to a hostel where she had a reservation. In Indonesia, immigration authorities took her (legitimate) visa papers away from her and threw her in prison for three days because, as they said, "Africans were ruining their country." She eventually was able to bribe her way out.

Koh Rong was a beautiful island surrounded by amazing white sand beaches and clear waters that I'm sure would have been amazing if someone had not stolen my passport from my hostel locker. So back up to the American Embassy in Phnom Penh I went.

Phnom Penh was described to us as a dirty, hard city, but didn't feel much different from any other southeast Asian city we'd visited. It had all the component parts: heavy scooter traffic, questionable street food, and pollution. The one key difference is that it seems to still be developing a nightlife and backpacker culture - reasonable given the country is coming into its second generation since a genocide that killed about a quarter of its population.

An interrogation room at S21 secret prison in Phnom Penh.

Phnom Penh boasts two main 'tourist attractions' to inform tourists on the bloody reign of the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979. The Khmer Rouge (known as Ankar, or "The Organization" to Cambodians) was a group of communist purists who believed in an extreme form of communism that drove all citizens of the country into rural areas to create an agrarian society.

The regime killed between one and a half and three million Cambodians in the course of only four years, and 23,745 mass graves have since been discovered. Under the Khmer Rouge, any offense from wearing glasses to having soft hands was seen as the sign of being an intellectual, which was enough to have one's entire family killed.

The photos above are from the regime's most notorious secret prison, S21 (or Tuol Sleng), one of the two main tourist attractions. It was converted from a school into a torture facility. Only 17 prisoners ever made it out alive, of the more than 20,000 who were tortured and forced to write false confessions there (including 2 unlucky Australians who sailed into south Cambodia at the wrong time.) Because the regime killed off all its doctors, it retrained soldiers to be doctors, who would clean wounds with saltwater, crush up "vitamin c pills" made purely of starch, and drain live prisoners of blood to give transfusions to soldiers. Most of what transpired at the prison is too graphic to relay here. It is a chilling showcase of the limitlessness of man's cruelty.

The second tourist attraction, in the photos above, is the Killing Fields (or Choeung Ek) outside of town. The monument in the middle, on the right, houses 5,000 skulls that were recovered from Cambodians of all ages thrown into mass graves. The philosophy of the regime was that an entire subversive's family needed to be killed in order to guard against any revenge, which didn't leave much room for Cambodians to survive under the Khmer Rouge. Finally, in 1979 the Vietnamese army invaded Cambodia to overthrow the regime and restore order, but many of the perpetrators of the genocide were never brought to justice.

What shocked me the most was the recency of the genocide. It was committed only 40 years ago, and 40 years after the beginning of the Holocaust. It's easy to convince ourselves that we would never let something so tragic happen today, but the western world probably thought the same after World War II and yet the Cambodian genocide still unfolded seamlessly 40 years later.

In my time in Cambodia, I noticed that locals lacked some of the joie de vivre that people had in Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia. Given the recent history, that realization made more sense.

Making friends running in Koh Rong.

Butterflies now fly over the mass graves at Choeung Ek.

Phnom Penh gave me food poisoning, so I spent most of my time towards the end of my Cambodia trip eating a healthy rotation of bread, fast food, and candy bars. One meal that I did get a chance to enjoy before my stomach was out of commission, though, was the bug sampler platter at Siem Reap's Bug Café. Two thumbs up! Some of the best tarantula I've had on the road.

Pictured above:

- The silkworm & cricket salad, with a light Mediterranean dressing.

- A stinging red ant pastry roll.

- Tangy tarantula samosa.

- Savory black ant spring rolls.

- A chewy waterbug with onions.

Delicious! (Except for the waterbug, which as awful.) As any great chef knows, the sauce makes the meal, and these babies were sauced up.

I took off from Cambodia through the land border with Thailand, not an easy feat given my new, Chinese knock-off-looking passport. On the night bus to the border, passengers had the benefit of comfortable double beds on either side of the central aisle. The one catch was that, if they traveled alone, they had to share these beds with one other occupant. It was a good way to make some last friends on the way out.

I left Cambodia with mixed feelings. On the one hand, I met some amazingly hospitable people and saw temples that impressed me in spite of my cumulative temple fatigue. On the other, my passport theft exposed me to the rampant corruption that underlies daily life there. And that is a story of its own.

Nik / 1.17.17

The Royal Palace in downtown Phnom Penh.

Fine establishments coming soon to Phnom Penh!