Africa lite

South Africa's is the story of two countries in one. When you travel through the main cities, it is easy to be struck by the first South Africa: large estates with expensive cars and verdant gardens. Along the perimeter of each garden run concrete walls with small wires that neatly fence each house in. On the other side of those fences, lies the second South Africa.

We spent most of our time taking in the country's scenery. The hikes to the top of Lion's Head and Table Mountain - rocky hills overlooking the western cape; the caves on the cliffs by Hout Bay that overlook the sunset over the Indian Ocean; the mountainous pass from Swellendam to Ladismith; the sprawling beaches in Plettenberg and Muizenberg and Jeffrey's Bay. It was easy to appreciate the amazing nature, strangely reminiscent of California's.

South Africa has the highest inequality in the world, per the World Bank's Gini rankings. In many ways, the situation has only worsened following the end of apartheid in the early 90's, though inequality has "deracialized." Still, the anodyne statistics don't do justice to the stark divisions between the townships littered across the country and the mansions that directly abut them. The multicultural "Rainbow Nation" seems to be a study in contrasts - beautiful beaches and sprawling vineyards paired with urban beggars and endless slums.

It was a riveting place to visit, and one that would be hard to describe without paying respect to both sides.

We spent our first week in Cape Town. My first day, I dropped my bags at the hostel Sarah had found for us, between the legendary Kloof Street and the foot of Table Mountain. I went to get groceries (read: water and wine) and, in the block between the hostel and grocery store, was stopped by two separate people asking if I knew where they could find jobs.

Cape Town draws comparisons to San Francisco and Rio de Janeiro for good reason. Wedged between the Cape of Good Hope, where the Indian and Atlantic Oceans meet, and Lion's Head and Table Mountain, it's hard to imagine a better setting to build a city.

Sunsets from the cliffs over Hout Bay.

Along the two main tourist strips in Cape Town - Kloof Street for the restaurants and Long Street for the bars - beggars dot the sidewalks. Almost unequivocally black, they approach disinterested western tourists as they walk buy, asking for food or change. It took time to learn, but I found that, anywhere you travel in Africa, it's good to have small bills, loose change, or even food on your person to give out. Our family friend Nancy, who hosted us, remarked on a friend who would always keep fresh fruit in her car for the beggars at each intersection in Johannesburg.

One of the more trying parts of backpacking in the third world is that you encounter poverty and suffering firsthand repeatedly, in the form of begging and street vendors. As a backpacker, you know that you have the capacity to help these people. And yet that capacity isn't limitless. The difficult part is making the conscious decision of who to help and who to walk past.

I walked past more beggars than I gave to on this trip. Many times, it was because I didn't have cash. Sometimes, because I didn't have small bills. But sometimes, I did have small bills but had just given some away, or wanted to give mine to someone else, or just felt cash-strapped and stingy. Coming out of a barbershop my first day in Cape Town, a kid who couldn't have been older than 12 came up and asked for food. I couldn't justify paying $15 and not sparing a dollar for food, so I took him to the grocery store and he bought two giant boxes of cereal and milk for him and his brother, dashing out of the store after I paid and he thanked me. There was no hard-and-fast reason to buy food for this kid over the next (other than, maybe, his age), but I found myself always rationalizing why I would give to one beggar and keep from another.

Hiking to the top of Table Mountain, overlooking Cape Town.

In South Africa, the dominant political party is the African National Congress - the ANC. Mandela's party has been in power since he became president and apartheid ended in 1994. Since then, the ongoing good will for the national liberation movement has buoyed ANC leaders to over 60% of the vote in every election. In spite of this, Jacob Zuma, the country's ANC president of 8 years, is deeply unpopular. We touched down in Cape Town the week that he let go of his finance minister - seen by many as the last honest holdout against Zuma's corruption. This would make for an interesting few weeks.

Lunch as Mzoli's, a butcher in the Gugulethu township north of Cape Town.

Mzoli's is now famous for its weekend DJ and braai sessions.

One of our tougher decisions in South Africa was whether to go on a township tour. We had grappled with the same decision years ago in Brazil, and decided not to take a tour of the favelas because it felt too much like voyeurism (or, as a girl at our hostel in Wilderness later put it: poverty porn.) Still, it would be wrong to visit a country whose recent history was so strongly defined by race and class struggle, only to see the white side of the story. On a few friends' strong recommendations, we took a tour of the Langa Township just east of downtown Cape Town.

Zuzeka, our tour guide, was raised in Langa and attended university, then returned to the township to become a teachers' assistant. On our walk, children from her classes would run up and hug her, or wave and call to her in the street for attention. We ran into her partner, a cheery and charismatic tour guide with whom she had a child, as we made our way into the town.

With our tour guide, Zuzeka, and Shooter, in his house.

Looks like we weren't the only famous people taking the tour - Shooter posing with Skrillex in his house.

Sarah and Dan try out Langa's locally brewed beer - mqombothi.

Langa's "Beverly Hills" neighborhood.

It would be hard to capture in writing the feelings that walking through a township evokes. The unwavering awkwardness of the cultural gulf between ourselves and the residents. Shyness on behalf of the tour participants, met with responses ranging from business-as-usual to open hospitality on the part of the locals. Heartbreaking insight into the living conditions people accepted as inevitable. Heartwarming glimpses of joy and laughter in spite of them.

On our walk, Zuzeka pointed out the town's free clinic with contraception and baby services, part government-sponsored, but mostly kept up through the sheer force of will of the town. The government, as it turned out, does not do much on behalf of townships. At least not until imminent elections. Along with the clinic, local schools all teach a "life orientation class" - a mixture of health and sex ed - to prepare students for real-world responsibilities. When young men come of age - 16 or 18 - they travel for a week into the bush with their fathers and fast, and only men know what happens there. When they come back, they have a new suit and hat waiting for them, which they wear for six months to signal their new manhood.

The houses in Langa are mostly shacks, built from scavenged materials such as wood and tin and all adjoining each other. No candles are allowed in the township anymore, due to a fire that started in one shack and burned down much of Langa in 2013, killing five and leaving 4,000 homeless.

Newly-moved families with three or four kids might all be packed into shipping crates while they wait for their houses to be built. The process, even for simple one-room houses, normally takes 10 years, or until the government is up for re-election. The shipping container shacks have no running water, and in winters when it gets cold, the houses get cold.

In spite of the absence of police and security, Zuzeka told us that the community is safe, mostly because neighbors can always spot or hear of crime, and everyone knows everyone. When perpetrators are caught by locals, they beg them to turn them over to the police, rather than face local justice.

We asked Zuzeka how the township felt about the tours - gaping westerners making the rounds through town, peering into houses and shops to take photos. By her account, the people of the township like the tours because under apartheid, the only white people in the township were police or military.

Still, not all is upsetting. The township also has a community library with a massive new theater, financed mostly by German service organizations. There is a section called Beverly Hills, consisting of nicer houses inhabited by the successful people from Langa. They come back to live in the township in order to give back, showing people that hard work pays off. The houses cost about $11,000.

Wherever you walk, small children run up to you and hug you, or walk in close clusters back from school, holding hands and whispering secret jokes to each other as they do. Kids play soccer in the streets and older men tease each other as they shoot dice and gamble on the sidewalks. Women laugh as they cook raw sheep heads out in the open. To westerners like us, small joys in the face of such poverty would be hard to understand. For the people who live here, it's just life.

The views from the top of Lion's Head hike in Cape Town. Dan, Sarah, and I somehow got ourselves to wake up at 5:30am to see sunrise from the top of the mountain.

One of our other days in Cape Town, we took the Tsiba Tsiba wine tour to Stellenbosch, on a (strong) recommendation from my cousins The Chiltons. Stellenbosch is Napa with better mountains and funny accents. I can't tell you much about wine, but we were quizzed early on, so here is what I wrote down:

- The vintage is when the grape is picked, not when it is bottled. (I guess this matters?)

- Spontaneous fermentation means that no yeast is added. Whatever that means.

- Darker reds are either full-bodied, or older wine.

The real revelation on the trip was that our tour guide was Candice Swanepoel's aunt, which I thought merited an introduction, though she apparently did not.

The views weren't all bad from the Tsiba Tsiba wine tour.

Another day in Cape Town, we took a tour of Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 of the 27 years he was behind bars. Prisoners were organized then the same way the country is organized now: into three racial categories, white, black, and colored. "Colored" in South Africa is a catchall term applying to mixed-race, Indian, and Asian (essentially: anyone not white or black.) The treatment of the prisoners varied according to race.

We learned at Robben of the early resistance leader Robert Sobukwe of the Pan Africanist Congress. When the apartheid government mandated that blacks had to carry their passports on them at all times, he organized a peaceful march without passports to police stations (which resulted in many black civilian deaths.) He was jailed, then upon his release date, kept on Robben overtime, not allowed to talk to anyone else in the prison. He was only allowed to read the paper and listen to the radio, so he could hear how the PAC was failing without him. He eventually lost his voice from years of not being able to speak.

Our guide also pointed out a WWII gun on the island finished only two years after the war was over - which our guide referred to as "Africa Time."

On Robben, political prisoners worked in mines for eight hours per day, five days a week, without tools or materials. Nelson Mandela had to get eye surgery from the limestone dust of the quarry. Initially promised they would only need to work for six months, the term was extended for 14 years.

The prisoners had a lunch and bathroom cave in the quarry that they got to use for a half hour each day. They turned this refuge into a university to discuss politics and teach each other what they knew.

Many of the ex-prisoners now choose to remain on the island as tour guides to demonstrate reconciliation. According to their accounts, they are now friends with the guards who jailed them. Our tour guide was a political prisoner in Robben for seven years, having been jailed at age 17.

Our time in Cape Town would not have been the same if it weren't for our friend Hetta's aunt Jane, who took us to a Sunday concert in Kierstenbosch, and Hetta's friend Sarah, a local helicopter pilot who showed us sunset from the caves of Hout Bay and the nightlife on Long Street.

Throughout Africa, you meet many interesting Europeans and foreigners trying to "make it" in Africa. Benoit was one such expat - a former Frenchman we met in Muizenberg who had been living in Joburg for the last decade, working throughout Africa for the mining giant Glencore. Benny had worked in Angola, Mozambique, and Congo running different mining operations until he decided to start his own equipment business with a friend - bringing used heavy machinery into the DRC, where the recipients sometimes don't even have roads to receive it. Like many white South Africans, he made a point of being rough around the edges, having told four kids who tried to rob him on the train a few days earlier to fuck off.

Chef Niko strikes again - making dinner for our hostel on the Stoked Backpackers rooftop in Muizenberg.

Benoit-led death marches in Muizenberg.

But actually - baboons are always where you least expect them.

The last street sign: Cape of Good Hope.

Like right here on the path next to us.

Looking back at the African continent from the tip of the Cape of Good Hope.

Following Cape Town, Dan, Sarah, and I rented a car and took it along the Garden Route - South Africa's version of driving the PCH. The California similarities were so uncanny that we made a guide for the places we visited phrased as their west coast corollaries to help translate:

- Cape Town, aka San Francisco - If for no other reason than the fog and hipsters.

- Greyton, aka St. Helena in Napa - A small, hidden sleepy town nestled into the Western Cape's foothills. With good local food and beer, and surrounded by farms and vineyards.

- Swellendam, aka Modesto - Churches, strip malls, heat, and not much else.

- Riversdale / Barrysdale drive, aka Nevada - A spectacular drive through dry mountain valleys, deserts, and sheer cliffs. Also the home of Ronnie's Bar and Sex Shop in the middle of the desert, and probably some Hills Have Eyes-type situation after dark.

- Mymering Winery in Ladismith, aka Palm Springs - Wine and cacti. One tennis tournament short of a perfect match.

- Wilderness, aka Santa Cruz / Bolinas - A small woodsy hippy community with a local market, good local eats, and killer surf beach tucked into the oceanside cliffs.

- Storm's River, aka Big Sur - The Garden Route home for anyone outdoorsy, with a bungee jump, zip lines, beaches, and the real natural Dijembe Backpackers'.

- Plettenberg, aka Carmel - Decently nice beaches, but honestly more of a retirement community than anything else.

- Knysna, aka Marin / Sausalito - Bougey brunches with a view.

- Jeffrey's Bay, aka Huntington Beach - Sooo many RVCA, Billabong, and Quicksilver outlets. Also, good surfing.

- Port Arthur, aka Stinson Beach - Where old people go to escape the hustle and bustle of the brash 50-year old set and perfect their lawn bowling game.

- Chintsa, aka Lost Coast - This beach is tucked away into the untamed Wild Coast, so it's only right.

- Durban, aka Los Angeles - We hear there are good beaches, but we only got to see the wide open, hot and dusty urban sprawl. Also, we went to a rugby game and the equivalent of a USC frat party afterwards.

In the middle of the desert by Barrysdale.

The Wilderness railway "station."

The Garden Route bible.

Lazy penguins lounge along Boulder Beach.

Hostel morning views in Wilderness.

Our winery in Ladismith.

Looking out over Plettenberg Bay.

Chef Niko cooking on three burners.

Beer tasting in Jeffreys Bay.

Catching some zipline action by Storms River.

The casual 709 foot bungee jump at Storms River that we did NOT do.

Naturally, when Dan and I saw this, we drove in to check.

Stopping to fondle some snakes at a snake farm.

Joining in the anti-Zuma protests in Port Arthur.

These guys really like to protest.

The entrance to the Apartheid Museum in Joburg.

In the museum, you are assigned a race for your stay.

One of our days on the Garden Route, the country of South Africa decided to stage nationwide protests against Zuma's government and the ANC. Stopping by one of the protests at Port Arther, Dan and I learned that the latest scandal involved Zuma's brokering with the Gupta family, a family of Indian-born businessmen with ties to Zuma's wives and daughters, who are trying to get Russian companies into South Africa to use the country's uranium for nuclear power. The South African people are apparently against nuclear power. This has all the makings of a great scandal.

The next elections are in 2019, with Zuma expected to step down as the president of ANC this December, under popular pressure. Zuma was a revolutionary with Mandela, and served 10 years in prison alongside South Africa's beloved leader. This credibility got him elected in 2009, but he has become progressively more and more unpopular with whites and blacks alike, following charges of rape, corruption, racketeering, and fraud. During my last days in Johannesburg, when I was supposed to leave for Zimbabwe, a nationwide bus strike held up traffic around the country to protest Zuma.

Along the Garden Route, one of the trips I wanted to make most but didn't get the chance to explore was visiting Lesotho (pronounced, somehow, Leh-soo-too), a small mountain kingdom that is its own country locked in South Africa between Durban and Joburg. The country, which gained independence from the British separately from South Africa in a bloody revolutionary war, is significantly poorer than its surrounding neighbor. We were warned that the highways turn to dirt roads in the country, somewhat like the American Indian reservations back home, and required a stronger car than our road warrior - the white Camry. Yet it is supposed to have some of the most beautiful mountains and hidden waterfalls in the country, and a tribe still much more insulated from the world than South Africa.

On our drive from Durban up to Johannesburg, Dan, Sarah, and I encountered a racist woman who ran the highway shop we stopped at to buy biltong. (For those who haven't had it, biltong is American beef jerky's overachieving brother. It is essentially beef sushi, and the one food item I would take back home with me in bulk if I could.) The woman, working the counter of her shop, went on an unprompted speech while ringing us up. "Everything is all about apartheid these days," she said, "But you never hear about what they (ie: the blacks) do to us. You shouldn't spend too much time around them. There's so much violence now where there never used to be. Robbing. Raping." This was all said while we waited for her to finish ringing us up in silence, during which a black woman came up to buy a candy bar and the shopkeeper said, "Give me a second, let me take her money first," before continuing on. The weirdest part of the tirade wasn't what she was saying - it was that she wasn't ranting to us. She phrased it as if she was giving us travel advice, as benign as where to surf or eat.

Later on, we met up with a friend of Dan's named Fathima who lived in Johannesburg. Fathima, of Indian descent, mentioned that she avoided rugby games, which tended to attract, Afrikaaners (the white Dutch descendants who made up the apartheid government) because of racism. It seems that race relations are a violent, endemic problem in South Africa. Maybe it was this dynamic that led me to feel safer everywhere else I would travel onward in Africa - even though there were fewer westerners and around. In South Africa, I learned, 500,000 women are raped every year with the average woman more likely to be raped than complete secondary school. Coupled with the tenth highest murder rate in the world, and it's hard to ever feel completely safe.

In Johannesburg, we stayed with my family friend Nancy Nay, who hosted us in the posh expatriate (white) neighborhood of Sandton. Nancy, who works for the Center for Disease Control, and her husband are both Americans, who raised their children around the world in South Africa, India, and Vietnam. Speaking both with Nancy and with Judy, her house help, you get the sense that South Africa somehow used to be much better. As per Judy, there was better public infrastructure (such as zoos) and cheaper goods and services (such as taxis and food.) Now there is more violence, infrastructure is falling apart, and prices are high. But Judy, who is from nearby Bulawayo in Zimbabwe, still chooses to work in South Africa to support her family back home.

"What village are you from?" Judy and her family are actually not from Bulawayo - but from a village nearby. Bulawayo is the closest reference point for tourists like me. The Africans we meet on the road never seem to ever actually be from a city, but from satellite villages nearby. It reminds me of a Serbian girl who asked me once what village my family was from in Serbia. I didn't know. My dad was from Belgrade. My grandmother was from Ćuprija. But was that a village, or a town? Americans don't have villages.

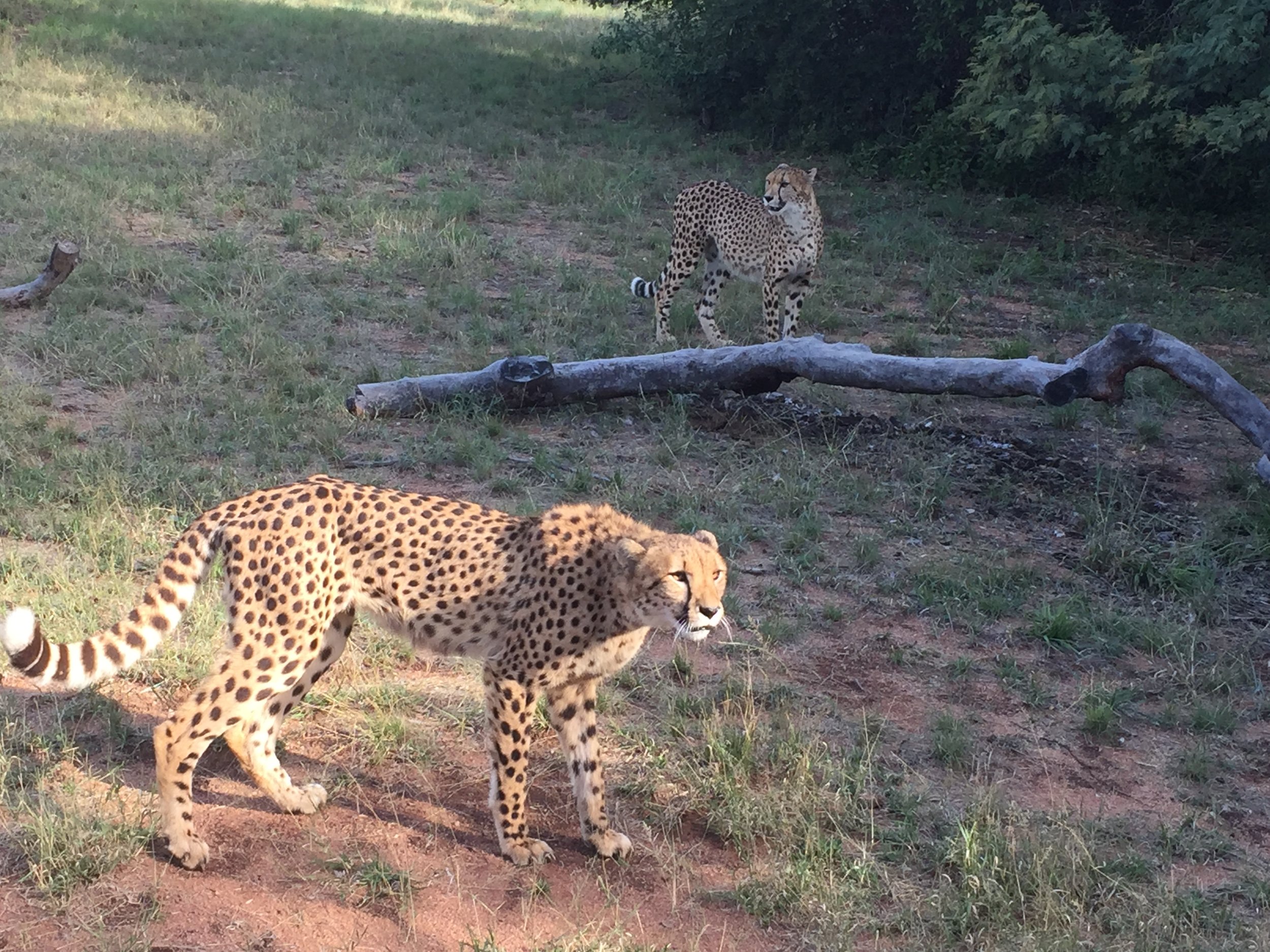

One of my last days in Joburg, while Nancy was mothering me during my two-week fever, we went to visit a cheetah sanctuary north of the city. There, we got to watch the guides feed cheetahs, hyenas, and wild dogs. And rolled around in a giant cheetah mobile.

Everywhere around the country, you see white vans with South African flag colors picking people up the townships and dropping them off in the cities. This system of "buses" used to be the only way for blacks to travel, as they were banned from using government buses. Even today, most townships still use them because they are cheaper than public transit. As per Trevor Noah's biography, during apartheid, they were dominated by gangs, split between the rival Xhosa and Zulu tribe whose conflict dominates so much of modern South African history. It was easy for us, as westerners, to imagine South Africans as one undifferentiated mass of blacks vs. whites, but as we learnt, tribal rivalries and today cause immense suffering for modern townships.

For anyone traveling to Johannesburg, the Apartheid Museum is most important feature of the city to visit. Among other things, we learned that Gandhi lived his early life in South Africa, and left to India to preach non-violence after studying it in Africa.

Throughout the country, in shops, cars, malls, and buses, you hear the sounds of Christian rock and Gospel played in the background. In fact, as I'd come to find, Africa is deeply religious, not in the nominal way of Catholic and Protestant Europe, but in the way of deep belief and participation. The country's Zion Christian Church amasses millions of its members around Mount Moria for an Easter pilgrimage each year, and borders all but shut down due to the high traffic of Africans from Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia heading home for Easter. In our tour of Langa, two men in thawbs came up to our tour guide to proselytize the word Islam, but she waved them away, later explaining that Islam was beginning to grow slowly in South Africa, but was struggling in the heavily Christian country.

One of our final days was spent touring the township of Soweto, one of the largest in the country, which feeds into Johannesburg. As our guide Phili explained, "when Soweto coughs, the whole world catches a cold." In the 1960's, the government installed street lights in the township that would enforce a mandatory curfew for all residents when they came on at 9pm. Even so, many homes in the township only got electricity in the 1980's. The townships started out as almost exclusively male, but women and children were eventually brought in to minimize violence and fighting.

We learned that private schools in the township cost 160 rand (about $12) per month, including meals - and yet that is prohibitive to many residents, who opt instead for free public schools. We also saw a block of new apartments, built for the township by the government in 2010, which then turned around and told residents that they would have to pay 850 rand a month ($65) for rent. When residents said they couldn't afford the price, the government refused to lower it and so the residents boycotted the apartments. Today, 500 units stand empty in the crumbling township, window dressing for tourists during the World Cup and nothing else.

Sarah's pied a terre for the night in Addo.

Our guide Fili, above, and the Soweto Township.

Getting bike-jacked in Soweto.

South Africa was an amazing "first step" into Africa, the same way Thailand was for Asia. It was safe, navigable, established for backpackers and open to westerners. The history was immense and the nature was breathtaking. But it left me with an acute sense that I was still missing something, that a more "real" Africa still lay to the north. And so, after a week of mothering from Nancy and a small upper respiratory infection, I bought a bus ticket for Bulawayo and set off into Zimbabwe.

Nik / 4.23.17