down the Nile

A green valley snakes through the middle of the desert, stretching to the horizon. As you fly north into Egypt, the Nile unwinds itself under the plane, cutting a wide swath through an otherwise blank and silent Sahara.

Cairo stands apart from that desert as anything but silent. Though the official population is roundly pegged at 10 million, the unofficial counts of the slowly sprawling slums that make up its fringes go as high as 30 million - a third of the country's population. Traffic permeates the city, where all the buildings are sun-dyed to the same tan color, composed of lethargically chain-smoking cab drivers who ferry its millions of inhabitants from one side to the other.

The Nile cutting through the Sahara.

The base of Cairo Tower in Zamalek.

The crowded streets of Khan Al-Khalili market.

Yet the city has become crowded since the military retook power and began to thin out business and traffic. White-suited and mustachioed officers stroll the streets, a symbol of imposed order. When we hopped into the back seat of an Uber the driver hurried one of us into the front so that he wouldn't have to pay police officers a discretionary "Uber tax." The heightened level of security, even if only for show, is plainly visible in the myriad metal detectors that announce the entrance to every building - even though many don't work.

Egyptians are haughty about their culture - as one tour guide told us, Egypt was under foreign rule for 2,000 consecutive years. They endured Greek, Roman, Islamic, Ottoman, French, and British rule, but each invader walked away more influenced by the Egyptian way of life than the other way around. Things in Cairo run at their own pace, and it almost feels as if slowness, disorder, or indifference is intentional.

Downtown views from the Cairo Tower. Our hotel, also on Zamalek, is towards the upper-righthand corner of the island. The Al Gazira club's soccer fields sit directly below the tower. (p/c for the better photos goes to Paloma Clohessey)

When you get off the plane, you see Joseph Tito street running along the airport - a reminder of Egypt's past commitment to the non-aligned movement alongside Yugoslavia, India, Indonesia, and Ghana - a bid to resist the dominance of the two power blocs during the Cold War. It reminds me of Dar es Salaam, where Barack Obama Drive runs along the city beaches.

In Cairo, we made camp at the Om Kolthoom Hotel, an old building that you can tell had prestige when it was built but was now comfortably sinking into obscurity. Still, on a clear day from our riverside apartment we could see across the Nile all the way to the pyramids. The hotel is located on the island of Zamalek, which cuts the Nile neatly in half as it passes through the center of town.

Views of the Citadel in the distance from walking through Al Azhar Park.

Al Azhar's restaurant opens out onto the Citadel.

Zamalek also serves as the de-facto center of much of the city's nightlife. When we arrive at our hotel, whether 1, 2, or 5 in the morning, we come back to cafés on the ground floor alive with men joking, yelling, and smoking. The women, who themselves normally go out with men earlier in the evening, are by then gone. The streets smell of coffee, shisha, and cigarettes - the main food groups of the cafés.

In our first days, we met up with our friend Mo, who traveled from California to meet us and take us to the wedding of a family friend on the outskirts of the city. Grabbing the tuxedo I had bought tailored for $100 in Dar es Salaam, we jumped into his cousin's car and sped off across the city, through Giza's 6th of October neighborhood, so named for the commencement of the Yom Kippur War against Israel. As we pulled up to Giza's JW Marriott, we realized that, as evidenced by the video below, we had not arrived at an ordinary Egyptian wedding.

After the wedding - at which Egyptian singer Amr Diab made an appearance to perform, and the bride's mother, also a singer, performed a new song she had written about giving her daughter away - it was time to see the real Cairo. Luckily for us, Mo's cousin Seif was all too eager to be a committed tour guide.

Egyptian hospitality and honor are a serious matter. By the proud customs of Egypt, hosts are expected pay for everything their guests indulge in. With Mo and Seif, there was no exception. Even though we had known Mo (who his Egyptian friends joked was "Americanized") for years, the locals were firmly insistent on being magnanimous hosts.

Walking by the Al-Rifa'i Mosque, where the Shah of Iran lays buried.

The citadel seen from the Al-Rifa'i Mosque.

During a tour of the pyramids, one of our guides talked to Mo about having two friends visit him in Cairo. When they arrived, his mother cooked them all a gigantic dinner. When they went out for food the next day, the friends insisted on paying for the guide, even though it was his home town. Though our guide protested, the friends were insistent, and our guide was eventually forced to leave the restaurant through the bathroom window to save face.

The honor culture is pervasive throughout; taxis will frequently tell riders to pay what they think they owe for the ride. When riders try to tip, sometimes the taxis will refuse on principle until the riders cajole them into accepting it. There are seemingly no agreed prices for any good or service, and haggling is an expected aspect of doing business. It is the kind of social construct that I imagine would drive a Scandinavian crazy.

Seif was full of other such small stories of Egypt's idiosyncrasies. While waiting at the American embassy to obtain a visa, Seif overheard another Egyptian who wanted to travel to the US. When asked why, if he didn't speak any English, he wanted to visit, he asked why all tourists comes to Cairo when they don't know a word of Arabic.

Cairo is colloquially called the city of 1000 minarets, and while there are supposedly 2,500 separate mosques in Cairo now, there are 65,000 in all of Egypt. The scattering of minarets around the world is such that a muezzin can call the faithful to pray at every hour of the day, so that Allah is never without reverence.

One day of touring, we visited the Citadel built by the Ottoman Empire atop the hills overlooking the Nile and its city. The Citadel, which looks like a structure pulled off the pages of Game of Thrones, was built by the first Sultan of Egypt from the Crusades era, Saladin. Its mosque was later built by Muhammad Ali (whom Wikipedia has to refer to as Muhammad Ali of Egypt for disambiguation), an Albanian commander in the Ottoman army who rose to the rank of Khedive of Egypt. Today, he is buried alongside the exiled Shah of Iran in the mosques of the Citadel.

The Citadel itself was built with many stones imported from the pyramids, which sit across the city of Cairo in Giza, visible from the Citadel's walls. It's an interesting reminder that our attitudes and those of our ancestors towards history were not always the same. The Ottomans came, viewed an expanse of 110 pyramids, and saw nothing but stones with which to build their capital. Today only 30 pyramids remain in the area. It is said that the Sphinx lost its nose similarly, when some of Napoleon's errant troops fractured it while practicing their shooting. But maybe we are not so different now - when visiting the pyramids, we turned to see a small boy who sold tourist tokens taking a break to pee on the side of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Our tour guide and Rob at the Citadel's new pulpit.

An ornate grave in Cairo's City of the Dead.

An ancient church at Al Mokattam.

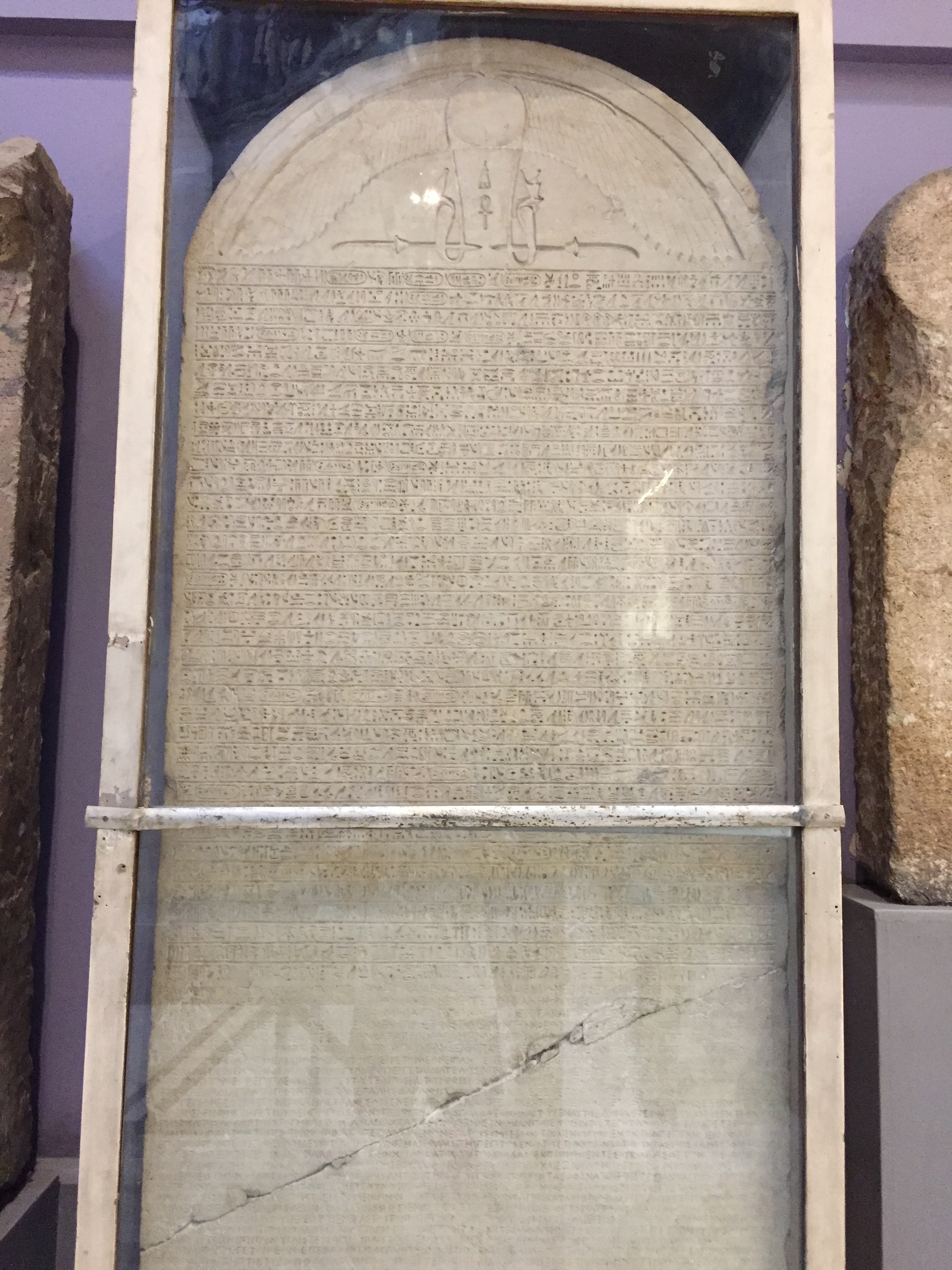

The Egyptian Museum guards told us that this was the Rosetta Stone, but some Googling confirmed that the actual stone sits in the British Museum in London. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Still today, Egypt retains many of the cultural influences of the Ottomans. The word 'Besha,' used like 'sir,' a sign of respect from the word Pasha, an Ottoman ruler. In the books of Naguib Mahfouz, the protagonists talk about how those Egyptians who think too highly of themselves will always brag of their Turkish roots. Even the Arabic of Egypt is notably different from that of the Middle East for its Ottoman notes.

On the tour of the Citadel, which Malcolm X visited in 1964, we learned that the builders had installed the pulpit, the largest in any mosque in the world, in the wrong part in the mosque. Pulpits are meant to be in the closest position to Mecca, yet the builders had installed it about 15 feet further than it could have been. So, without missing a beat, they installed a new smaller one 15 feet closer, and now the larger remains unused.

One of the sights of Cairo, a large cathedral of Jesus carved into the walls of cliffs that jut down from the hills overlooking the desert, is only accessible through Manshiyat Nasser, or Garbage City. Here, an entire neighborhood sits piled high with trash, with an entire local economy built around scavenging for valuables in the refuge of Cairo's 30 million inhabitants. The owners of this trash empire are said to collect millions in earnings from scavenging every year.

One of the most notable features of Egypt is that it is not clearly the Middle East, not Africa, and not the Mediterranean, but instead an almost paradoxical combination of all three. It straddles these three global cultures in a natural way, adopting elements of each. The food and language of the Levant; the cosmopolitanism and bon vivance of Italy and Greece; the freneticism and openness of the sub-Sahara.

Kids play soccer in front of the Abdeen Palace, while military guards watch on. The front of the palace, normally busy with people, stands almost deserted now.

A street by our hotel in Zamlalek. Most of Cairo looks like this.

Finding a contemporary art shop with a VR headset and tech hub in old Cairo.

We spent a day with Mo lounging at his old pool in the Al Gazira Club, the Zamalek equivalent of a country club. His uncle used to be a polo star at the club.

The Egyptian Museum.

My taxi driver teaches me how to spell my name in heiroglyphics.

One of the many party feluccas on the Nile at night.

In Cairo, the world is colored the same and covered with a thin layer of dust. There is almost a feeling that even the corner stores and restaurants pre-date modern civilization, sitting under their thin layer of desert sand. And everywhere through the city, you can see the name of Omar Khayyam. Khayyam was a Persian polymath, mathematician, and poet, immortalized for his laissez faire perspectives on drinking, enjoying oneself, and the afterlife. As such, many bottles of wine and floating Nile club barges bear his name. "Drink wine. This is life eternal. This is all that youth will give you. It is the season for wine, roses and drunken friends. Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life."

In many ways, Egypt feels like a time that was lost in the rest of the world. Taxi drivers offer you a cigarette when they light one up themselves as they drive, like they may have done in Europe 20 years ago.

While in Egypt, we also had a chance to visit Alexandria, famous for its lighthouse. The building, one of the ancient wonders of the world, was one of the world's tallest buildings for centuries at 500 ft., until it gradually eroded to time and earthquakes, its last stones appropriated to build a citadel in 1480.

The king's summer palace in Alexandria.

The newly built Alexandria Library, the world's largest reading space.

Anwar Sadat's Nobel Prize in the library.

On one of our last nights in Cairo, we went to watch Abla Fahita, a television show starring a puppet that mocks all aspects of Egypt cultural and political. The show became a hit with the country after Bassem Youssef - billed as Egypt's Jon Stewart - was chased out of the country for his biting satire of the government. Abla Fahita herself, a puppet modeled after a sexually liberal older lady, has not spoken without controversy, and the show steers in a slightly more anodyne direction after the risks it incurred when it openly mocked members of parliament.

Seif hangs out with us as we wait for Abla Fahita (shown in the background) to open up.

The view from our room at the Om Kolthoum.

With our time in Egypt drawing to a close as slowly as the snaking of the Nile, Dan and I set our sights on our upcoming trip back to America. It had been my longest time ever spent outside of the US - 8 months - and though I felt I could keep on traveling indefinitely, the cumulative fatigue and one last bout of food poisoning had me excited for, more than anything else, the feel of home.

- Nik / 7.8.17

Views from the Abu Dhabi airport, my connection where my emergency passport got me in trouble one last time.