the muzungu trail

Tanzania isn't actually a natural place name, like Malawi or Zimbabwe. The country and its name were born when two nations, Tanganyika and Zanzibar, joined together. Locals are quick to correct my western pronunciation - Tanzanía - with the proper inflection - Tanzánia.

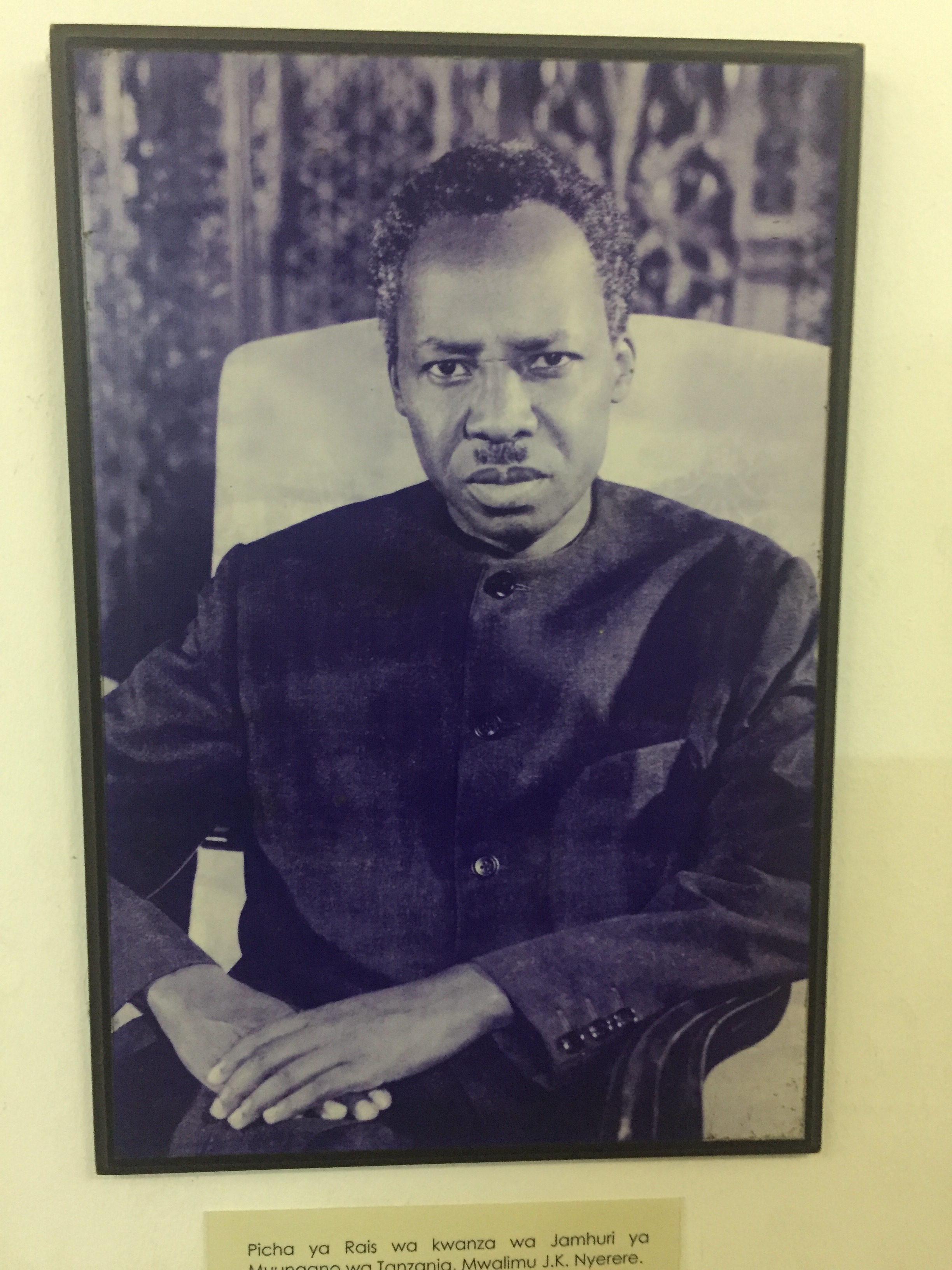

The people of Tanzania still reveres the country's first president, Julius Nyerere, who brought the two countries together and into independence from British rule. Tanganyika - the large swath bordered by Burundi, Rwanda, Congo, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, and Malawi - and Zimbabwe - the small tropical island off Tanganyika's coast - started as separate republics. But Nyerere, who ruled and modernized the country from 1960 to 1985, brought them together as part of his greater vision for the east African region.

Nyerere adeptly played both sides in the cold war, enriching Tanzania off the east and west. He met with Jimmy Carter while inviting China in to build the TAZARA railroad, which I took across the country to Dar es Salaam. He also institutionalized pride in Kiswahili (or Swahili), the language in which he taught history before he went into politics. As a result of his legacy, Tanzania is one of the few east African countries that largely does not speak English - an element that made traveling through the country interestingly challenging. And of those locals who do speak English, many are at a minimum trilingual - fluent in Swahili, English, and a regional dialect local to where they grew up. To maintain Nyerere's legacy, Tanzania recently discarded English as the primary medium of education in its schools in favor of Swahili. While it may not help the country's international ambitions to handicap its business languages, this legacy is part of why westerners are familiar with so many Swahili words, of all the dialects in Africa.

Swahili itself is an easy language to pick up quickly, as if designed to be so. Like Japanese, almost all consonants are followed by a vowel. "Mambo kaka, habari?" (What's up brother?) "Unaenda wapi?" (Where are you going?) "Hapana asante." (No thanks.) "Karibu sana." (You're very welcome.) "Chingapi?" (How much?)

Maybe it was this simplicity and ubiquity that led to Swahili - also the language of Kenya - to be the Lion King dialect. Hakuna matata (or hakuna shida) actually do mean no worries, simba translates to lion, pumba to warthog, and rafiki to friend.

President Nyerere, seen in his official portrait at Dar es Salaam's National Museum.

I began my trip in the border town of Mbeya, a 'small' town of 280,000 that sits in the mountainous plateau of southwestern Tanzania. As you drive from the Malawi border up the mountains into Mbeya, the landscape looks closer to what you'd expect in Finland than rural Africa. Foreigners began planting tropical pines decades ago, and now some development groups work with locals to maintain robust pine plantations throughout the plateau. Up in the mountain chill, locals trade the colorful pattern dresses of southern Africa for the the checkered cloth warps in the fashion of the Maasai.

The TAZARA railway, built in 1976 by the Chinese, cuts across the country from Zambia, uniting the two, and runs from Mbeya in the west to Tanzania's capital, Dar es Salaam, in the east. Yet the train only runs the corridor twice a week - a nicer, newer express train on Wednesdays, and an old slow train from the time of the railway's construction on Saturdays. I chose the Saturday train, which winds its way over two days towards the capital, through gameparks where it is rumored that passengers can see the Big Five from the safety of their railcars.

I showed up at the station around 10am for the 12pm train, ready to buy a ticket. As is so characteristic for all things African transport, the train was delayed to 9pm and the ticket vendor, who wrote out tickets by hand in the big, empty station, was out of first and second-class tickets - the two berths with beds in them - so third class it would have to be.

Standing in line for tickets, I overheard the only other white person in the station talking to a local behind me about traveling to the country to sell cocaine. As it would turn out, this was the run-of-the-mill irreverence of Nicola Fontanini, an Italian who I would travel with for the next few days.

With nothing to do for 9 hours, we got a local named Gabriel to take us up into the mountains to hike the Ngozi Crater, which houses Africa's second-largest crater lake. Though the crater was created by a gigantic extinct caldera, which last erupted around 1450, local lore maintains that it was created by a meteorite. Evil spirits are still said to live within the lake - possibly explained by the occasional limnic eruptions of poisonous carbon dioxide from the lake floor. Standing on the caldera's edge, looking down its steep cliffs to the placid lake in the quiet of the jungle, it's possible to believe in spirits and ghosts as clouds slowly descend and obscure the lake by night.

Coming down from the crater, Nicola and I found ourselves with a few hours still to kill before our train departed, so we took Gabriel out for dinner. Like the rest of southern Africa, a good dinner in Tanzania consists of corn meal, rice, and meat. Over a few beers afterwards in the slum where Gabriel lived - for $50 a month in rent - he told us about life in Mbeya. Few people from the town ever left, except to do business within the region and then return, in spite of a big local university there. By the university, local girls unable to pay for their books occasionally prostitute themselves at night to pay for school; as Gabriel tells it, the going rate is 5,000 Tanzanian shillings a night - about $2.50.

The view from the front of the spartanly-designed Mbeya railway station along the Tazara. The Chinese built Tanzania's rail stations in the large, unadorned fashion of communist engineering.

Our view down into the Ngozi Crater lake from the cliffside. As we sat looking into the silent lake, fog slowly descended into the crater, obscuring our view.

The Mbeya railway station by night, barely lit, with vendors selling chipsy - fried eggs made with french fries and ketchup - outside.

Grabbing a drink from the 'bar' in Gabriel's neighborhood - the front porch of a man's house where he put a stand and fridge.

Our third-class accommodations.

Nicola and I boarded the train when it came into the station around 10pm and, finding nothing else to do, finished off a bottle of Konyagi - the ubiquitous Tanzanian gin - before sneaking into an unoccupied berth to sleep for the night.

The next day, as we snacked on crackers from the bar cart, Nicola told me his travel story. About eight months prior, he had left his home in Trieste, Italy, by hitchhiking his way through France and Spain. There, he had taken a ferry to Morocco and hadn't looked back, traveling overland through all of west Africa. His stories made me realize that, even traveling simply as I was, my African adventure was nothing compared to his. In Mauritania, he spent a month living in a village next to the large abandoned coastal wrecks of old freighter ships. There, poor locals lived within the ghostly, rusty wrecks and scavenged for food. Families commonly had indentured servants, daughters sold by their fathers into servitude so that someone would feed them. In poor Guinea Bissau, even the capital didn't have paved roads, and he packed into a crowded minibus for 36 hours as the driver blasted Christian hymns, bouncing over potholes and muddy ruts. In the war-torn Côte d’Ivoire, he stayed in a village during an annual rite where locals could not leave their homes at night because of a killing spirit who wandered the area and killed anyone out late. Nicola hypothesized the spirit a man in a mask drunk or drugged up, but when he heard a voice in the woods walking alone late one night, he sprinted home to avoid finding out. In spite of his style backpacking - about the roughest I'd encountered - he never felt unsafe. He only had a knife held to his throat one time, by a man who he'd paid to help him find an open bar one night in Togo, and had lost his phone and gone without any way to be reached for five months.

Enjoy Coke - the Swahili way.

This sign is the only preventative measure that keeps you from falling off the back of the train.

The TAZARA train passed through rural Tanzania with us on it for the next day, and the day after that, as I had heard it would do, breaking down on the way and depositing us in Dar es Salaam in the early morning a day late.

Dar is a gigantic, sprawling melting pot of cultures. When Hollywood movies pan to scenes of bustling, chaotic streets with frenzied general 'Africans' baking in the sun, it is Dar es Salaam that provides the stock footage. Thanks to Nicola, I learned to use the dara dara system of minibuses, which will take you anywhere through the cities of Tanzania for about $0.25. You hop on, crammed in with other commuters, and keep traveling in one direction until you hop off and take another along the next vector you need to travel.

Packed into a dara dara behind a woman sitting between two seats. These minibuses often put buckets down in the aisles to accommodate extra sitting passengers.

Tanzania's local brand of beer...

...and liquor. The label "The Spirit of the Nation" used to read "The Tear of the Lion."

In central Dar es Salaam, the smell of spices follows as you walk down the street, much like the back of a bodega in DC or NY or SF. With a few days to wander the city, I noticed I was the only muzungu around. The word muzungu is the ubiquitous eastern African word for "white man," with Chinese and Indians meriting their own epithets, but generally grouped into the catchall. Literally translated, it means "someone who roams around aimlessly" or "aimless wanderer," which was perfect for me because that is what I was doing.

Dar es Salaam does not have much in the way of a tourist scene or infrastructure, but it does provide much to wander through. The city has a noticeably Islamic cultural influence - Dar es Salaam means the "place of peace" in Arabic - different from the western steppes and the southern countries that preceded it. Five times a day, the muezzin can be heard leading the call to prayer from the minarets throughout the city.

Nowadays, the city plays host to many Chinese, who bring foreign investment with them and work tirelessly to quickly build all the new skyscrapers downtown. A tuk-tuk driver pointed out the skyscrapers, notably different from the Tanzanian-built ones, as we drove through the city, and praised the Chinese for their efficiency and work ethic.

Dar es Salaam, maybe as as part of its business draw, also hosts sexual tourism. When I went out to dinner at the nice hotels, old white men would come to the restaurants with their young black women, and the not so nice hotels such as the one I stayed at hosted paid girls who would lounge in the bar downstairs at night waiting for clients. Women flock to Tanzania for sexual tourism as well, looking for the "nubian banana," and locals don't bat an eye at this business as usual.

Every team gets knockoff gear made in Tanzania.

One of the many mosques that crisscross Dar es Salaam.

The empty beaches of Dar es Salaam, littered with trash and supposedly dangerous for tourists, but great to run.

One delightful surprise of Dar es Salaam was the sight of Maasai walking everywhere, with their cloaks and long sticks, used to signify their status as warriors. In the dara daras and on the streets, you crowd in alongside southern and western Africans, ethnic Chinese and Indians, Maasai, Arabs, and Muslim Tanzanians, each going about their own business in this crossroads of a city.

The Muslims in Dar mostly sport the black marks of the devout on their foreheads, meant to show their self-flagellation against the prayer mats each day. Starbucks and McDonalds are mostly absent from southern and eastern Africa, but KFC has found a foothold throughout the area, even more ubiquitous than back home.

All buses and trucks have on them either holy phrases - Christian or Islamic - or the names of English Premier League football clubs - perhaps also meant as benedictions to protect their occupants. Each bus has signs that come standard, which proclaim the bus's seating capacity and say unambiguously No Standing - perhaps left there as a tongue-in-cheek joke as riders crowd the narrow aisles and seats. Traveling this way teaches you equanimity and patience, as I learned a couple times when my bus or tuk tuk would shut down its engines in traffic jams, and drivers would get out and socialize for an hour before traffic started to move again.

But nothing in my travel had prepared me for the Kariakoo market, in downtown Dar, which I visited each day in the city. The market teams with life - men, women, and children running the packed streets from stand to stand, alternately selling and buying. Here too, I was the only white person around, but drew little in the way of sideways looks as people busily rushed past. I knew that, in a little over a week, I would have to travel to Cairo to attend a wedding with my friend Mo, so I found a tailor in the middle of the market and haggled my way into a fitted tuxedo and some shoes for the wedding for $140.

With time to kill and not much else to see in Dar, I hopped a ferry from the city to that former second state, the island of Zanzibar.

My timing in Zanzibar was not exactly fortuitous. Eastern Tanzania has two rainy seasons: the 'short rains' in November and December, and the 'long rains' in April and May. I happened to visit right in time for the latter. From my ferry landing in Stone Town, the historic trading port of Zanzibar, I made my way over to the small east coast windsurfing town of Paje by dara dara.

Though rainy and flooded, life in Paje wan't all bad when I had it to myself.

In Paje, I had a sprawling hostel of beach and bungalows pretty much to myself. As the rains came through and chased away the tourists, I spent a day with an English girl, the only other guest, who had been working at a hospital in Dar for the past two months. Her stories from work were sobering enough to make me thankful that Tanzania did not make the long list of hospital visits through our itinerary.

In her hospital, workers would frequently use their work computers to download movies and pornography, which they would otherwise never have access to without internet in their hometowns. They would take 3 days, unabashedly, downloading movies and would then zip-drive them and take them home. Syringes in the hospital would automatically lock at the bottom so that hospital staff can't reuse them between patients, so hospital staff would instead make sure not empty their syringes to the bottom, so that they could get around chronic shortages of syringes. One day, a small boy came to the hospital with his hand chopped off; it had been taken by local police, who found him stealing chocolate from a store. She recalled the look on his face as he stared at the stump of his arm, slowly processing that he would never get his hand back.

At my hostel in Paje, I also met a middle-aged man staying at the hostel, who had moved from Belgium to Tanzania after going through a divorce and buying a plot of land for only a few thousand dollars. He planned to use the land to farm pineapples for the next couple years while he built an orphanage their for abandoned local kids.

In Zanzibar, women again trade the wraps of the Maasai for burqas and hijabs. Zanzibar is Islamic, much like the island Langkawi in Malaysia, but the dress code is stricter and more pronounced. Yet women still add flair to distinguish their outfits, with bright splashes of color on their veils and dresses. I got the chance to admire these outfits as I took a dara dara back from Paje to Stone Town, to spend the weekend before returning to Dar.

The poster in front of this residential area in Zanzibar town shows the discrepancy between how it was supposed to look and how it looks.

The old colonial-style buildings of Stone Town.

Bustling Stone Town is Zanzibar's main draw, and it's easy to see why, getting lost among the small roads of the old town. Many of the buildings date back to much earlier days, when Arab slavers and Dutch East India spice traders would frequent the port as they made their way around the world. The town boasts a beautiful mix of Islamic and colonial British architecture, with open piazzas in the old hotels that sit on the water's edge.

My hostel, maybe the nicest I'd been to in Africa, played host to bored locals during the day who owned their own shops or hotels on the island and split their time between Zanzibar for tourist season and homes back west. One of them, Zishan, was living for a year in Tanzania, came to the country with Architects Without Borders to build an orphanage for children suffering from albinism. I had heard that albinism was a problem - and very rarely saw albino adults in my travels - but didn't realize how severe it was.

Throughout eastern Africa, albino children are kidnapped and harvested for their body parts, which are believed to have curative properties. Though it is de jure illegal, Zishan had been to some of the markets where children's hands and legs hung like so many animal parts for sale. Many mothers in small communities have two choices: raise their children and lose all community support (for albino children are thought to be bad luck), or abandon their kids to the black market. Even when raised by their mothers, many albino children go blind and die of skin cancer from African sun exposure.

The orphanage Zishan was designing has railings to walk along the halls, making it easier for blind students. Window slats let light into the rooms while shielding pupils from direct sunlight, much like a library or museum. And the building uses its trellises and the large, sprawling natural baobab trees to provide shade during breaks.

Scenes from exploring the beautiful scenery and architecture of Stone Town.

Hanging out at the hostel by day, I'd watch movies with the locals on the projector in the 'living room.' One show we began watching was Netflix's Dear White People, which was interesting to watch with Africans, who were incredulous that students of color were still treated the way they were at American colleges, something I had to confirm to them is still the case.

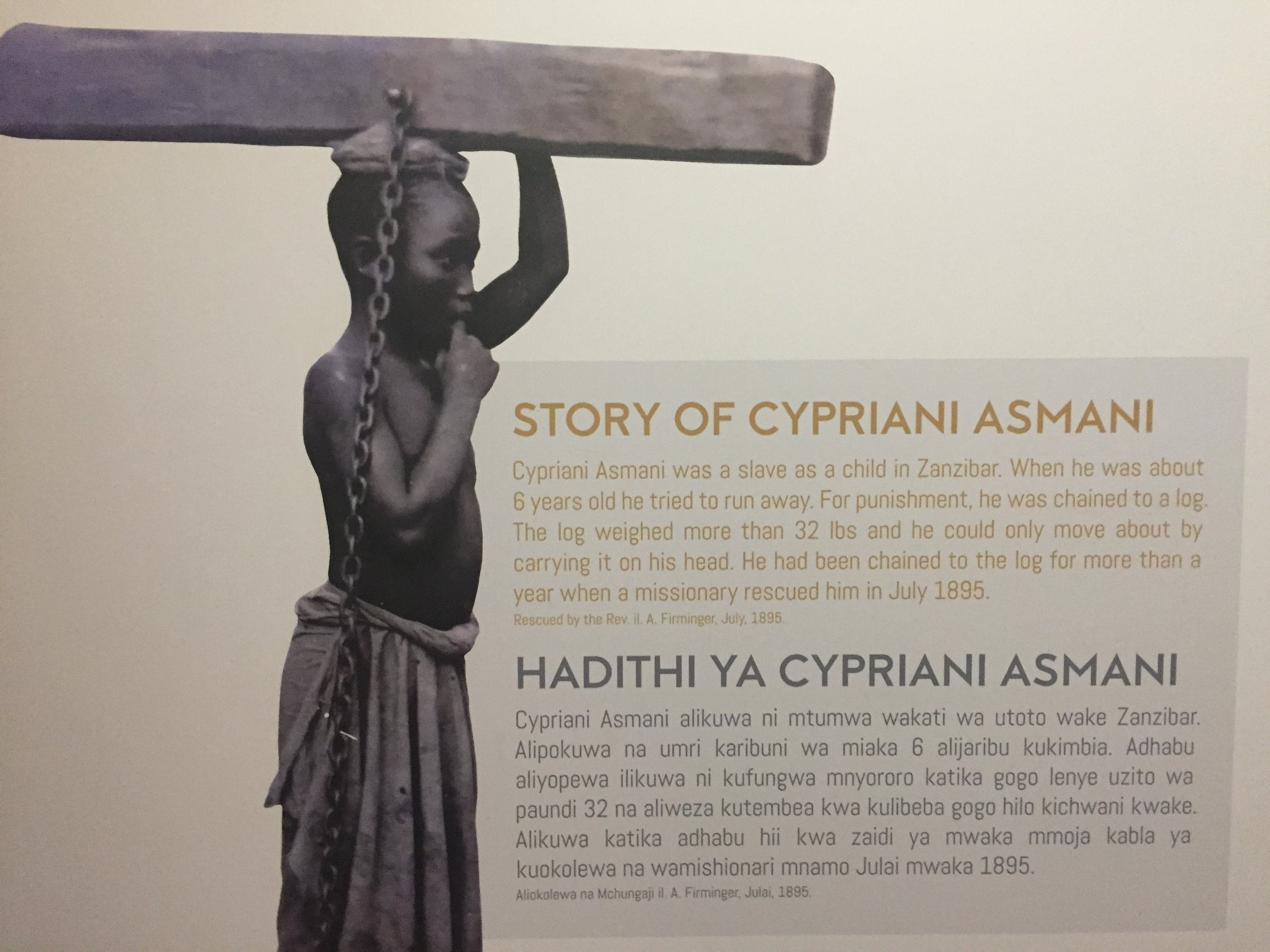

My last day in Stone Town, I took a tour of the large Anglican Church, which used to house the Zanzibar slave market before the English forced the Arab governor to abandon the practice of slave trade in 1879.

Before the church was built, a big tree stood in the middle of the market yard. There, once a day, traders would take a procession of slaves up from the cellars, where they had been starved for the past couple days. One by one, they would tie slaves to the tree and whip them. The more lashes a slave could take without crying out, the stronger they were assumed to be, and the higher the commission for the trader.

The Church, built once the trade was abolished in 1880 with Arabic influences in the architecture, retained a small circle in front of the altar to mark the place the tree had been. The church has a small a stained-glass window with a design in the likeness of the first African saint, but his body broke off the main window when repairmen took it down to clean.

As throughout the rest of Africa, the missionary David Livingstone's presence is felt everywhere. The two slaves who accompanied him until his death brought his body to England, where they were in turn made rich by way of compensation and came back to Zanzibar to buy land.

Like so many places we visited in our travels, Zanzibar has its own tragic history, yet the sunny island is now home to beautiful beaches and attractive tourists escaping the winters of the northern hemisphere. Returning to Dar, I spent one last rainy night in a hostel built by the Salvation Army before hopping a motorcycle ride to the airport for our last destination, my 20th country on this trip, Egypt.

- Nik / 6.15.17